Future Learning Spaces: Classrooms of the Mind

Tom Haymes

—

We like to think that learning takes place in a physical location. We call those places schools or colleges or universities. Often, we call those places classrooms. This is an incomplete picture. Those words describe places that can facilitate learning, but ultimately, all learning takes place in the mind.

We externalize learning because we have been trained to do so by more than a century of industrialized education. Digital thinking should liberate us from these logistical shackles, but that hasn’t happened yet. This disconnect is not a new thing. As early as the 1970s, Ivan Illich recognized how we commonly confuse learning with the physical manifestation of school when he wrote:

The pupil is thereby "schooled" to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new. His imagination is "schooled" to accept service in place of value.

If we disconnect learning from schooling, we can apply a much more flexible mindset to our design processes. This could have profound implications for how we design our pedagogy, programs of instruction, and technologies. These technologies include all the virtual and physical spaces that we can use to facilitate learning, not just the “gadgets” that may populate them. The key is to blend spaces and technologies into a continuum of tools that we can apply to any course or any individual who needs help to learn.

Our conception of “campuses” comes from the industrial notion of the factory. Factories don’t empower humans. They make us widgets in a machine. If you want more widgets, you build bigger factories.

Technologies often go through a period where they get bigger to maximize inefficient sources of energy and our ability to turn that energy to their purpose. In early aircraft, it was common to put more and more engines on a plane to generate more lift. Then we improved the engines and the ratio of engines to lift shrunk. The same is true for our educational technologies. Consider the cost and complexity of early Polycom systems and compare them to what you need to have a conversation in Zoom or FaceTime.

But this is also true on a systemic level. As we have attempted to scale education to a wider and wider portion of the population, the schools have grown to accommodate physical bodies in physical classrooms. It is high time we applied more efficient engines to our goals of connecting learners with knowledge and skills.

Remote teaching during the pandemic showed efficiencies are possible. Teaching and learning can happen wherever the student is. There is no iron rule that says the students must congregate in a specific physical location in order to hear the voice of the teacher.

Forcing students to gather excludes large parts of the population who cannot commit to being in the same place at the same time because of work or family obligations. It aggregates learning away from the individual, leading to less diversity through a reduction in individualized learning. These realities alone should lead us to question the current strategies for scaling education.

My experience as a remote teacher during the pandemic showed me the importance of community and collective engagement with the material that we were trying to learn. My students missed being able to congregate in person. What was missing, however, was not the classroom. It was the “hallway time” of informal spaces. We could move the classroom online fairly easily. Community time, however, was much more difficult to replicate. This realization led me to revisit the work I had done on informal learning for a local community college.

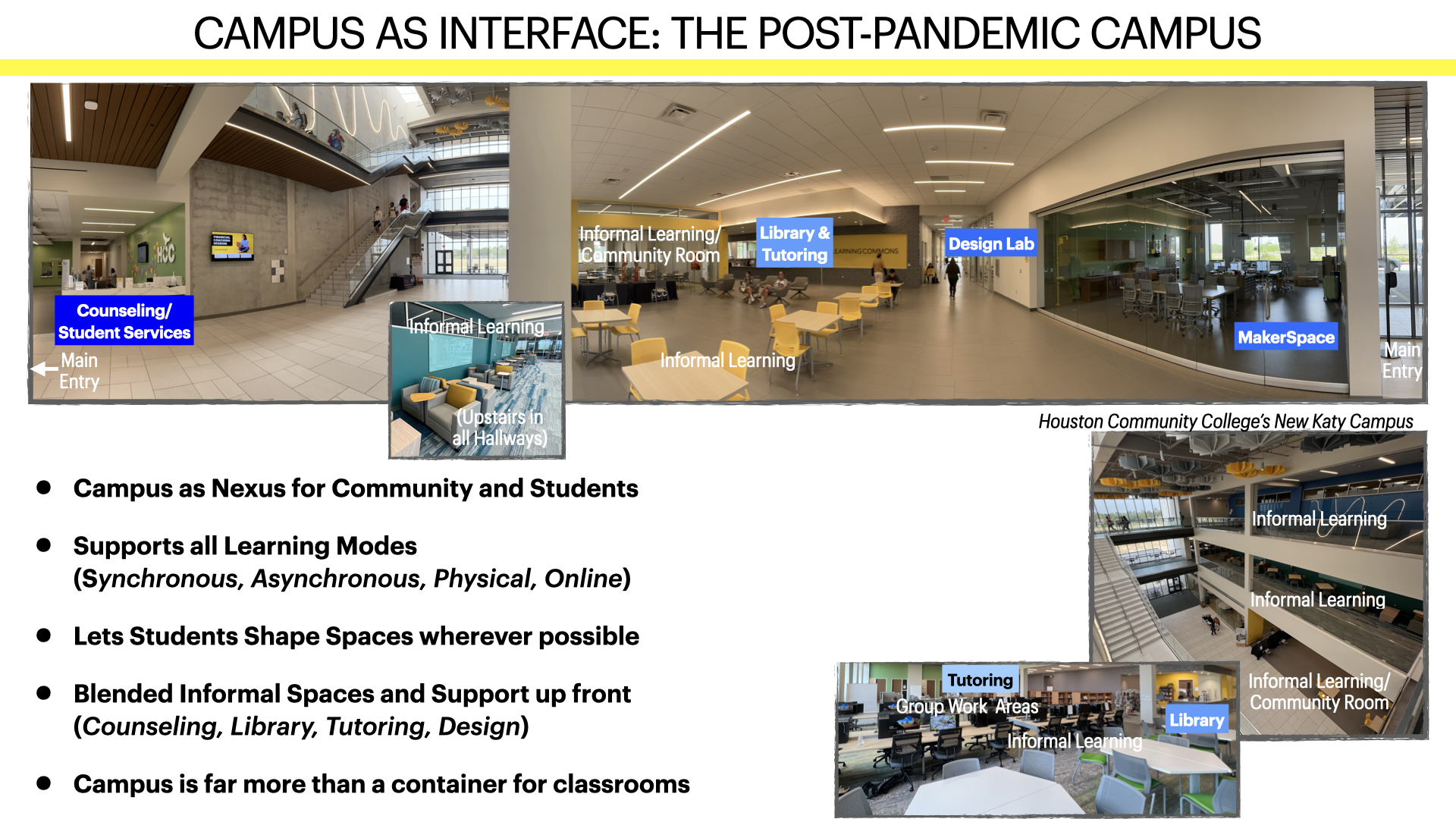

Immediately before the pandemic struck, I consulted on a new campus for Houston Community College. The brief for this campus was to maximize enrollment on a minimal footprint. Using classic measures of X number of student seats into Y number of classrooms that can be scheduled for Z number of hours did not work. This calculation showed that the desired enrollment was 50% higher than the space would accommodate, at least according to traditional measures.

Our approach to the resulting design was not to cram in more classrooms. Instead, we tacked in the opposite direction in order to maximize informal and support areas. This created a hybrid/blended environment where students taking online classes would find a place for collaboration and support. We would then effectively move much of the enrollment online but still create a hub for learning where learners could come together to form communities of practice.

This work led to many offshoots, starting with the STAC model and culminating in the Hybrid+ concept that I outlined in my 2020 book, Learn at Your Own Risk. The root of these ideas is that students need to be motivated and supported to engage in effective learning. This should form the underlying goal of any campus. Campuses with this design philosophy also support teachers that are trying to create individualized pedagogy.

That means that we should teach those things that require persistence, repetition, and convenience online. The campus would support everything from study groups to teacher-led small work groups to events that host outside experts. It would form a critical interface between students and the knowledge that they are seeking.

The other implication of this approach is that we need to rethink the nature of our courses. We should start by removing artificial distinctions between online and in person instruction. There is every reason to expect most courses to blend all modalities. The key distinction should be whether learning is expected to be synchronous or asynchronous, not whether it’s done online or in a physical space. All courses encompass both already. However, we don't make efficient use of online resources to maximize the impact of the limited amount of synchronous time students and teachers have together.

Courses are tools used to contain discrete bits of knowledge. We build walls around them. This is another legacy of the specialization of undergraduate learning stemming from the factory model. The logistics of classrooms mean they are a scarce resource and that drives enrollment calculations and scheduling considerations. If digital learning means anyone can seamlessly teach or contribute to learning in a course, what’s the point of segregation?

With a fluid course model, any specialist can come into the course seamlessly and enhance the experience of the students, deepening their learning. Creating this level of fluidity will require systemic rethinking of how we organize our spaces, time, and structures of learning. We can build to optimize resources in all three areas. We can already adapt existing technologies and spaces to experiment with how this might work. For example, I already have a librarian embedded in my classes using nothing more than the affordances of my Learning Management System shell.

The learning space of the future is the mind. The technology spaces we build around that should reflect the realities of how people learn more than the logistics of how we educate them. Physical spaces, like the new Katy campus, which opened in May 2022, should form part of a much larger suite of tools, technologies, and people that will support learning in all its forms. This will also give us new opportunities to humanize, individualize, and diversify the education journeys for all.