You’re all Different! I’m Not! - Open Loops, Systems of Learning and Collective IQ

Tom Haymes

—

It’s the beginning of the semester and I’m once again trying to bridge two incompatible systems. My students are used to closed-loop systems of education. They have had years of training in the rhythm of cram and exam (or some variation thereof). The “best” of them have mastered this pattern and start the semester trying to figure out my version of it. All of them see everything I/we do through this lens. The disconnect occurs when my class design doesn’t conform to their expectations.

The natural human reaction is to navigate the “maze” - and it is a maze - that I have set up with the minimum amount of effort necessary to get through it. Our students struggle to find meaning in the systems of education that have acculturated their habits of schooling. It is a rare student capable of looking beyond these structures. We program them not to.

One of my favorite scenes from Monty Python’s Life of Brian is the one where he tells the crowd “You’re all different!” and one guy says, “I’m not.” I feel like this a lot as a teacher. I try to convince my students that they need to engage in open-ended exploration, but they only want to know what I want them to do.

When I try to make the class expectations about them instead of me, they find this profoundly disorienting. My “final” is a web portfolio which they own. It’s a website on a server that they control. They’re creating a tangible artifact based on their own interests that they can use to show their communication and analysis skills to future classes or employers. They can take this assignment as far as they want. It’s an open loop.

Despite this, they never push the boundaries of what’s possible. Their focus is squarely on what is necessary. Necessary is always a closed loop.

Professional life today is not a set of closed loops. It is a set of problems, both large and small, that we must navigate. There are few instruction manuals on how to close these loops. The best we can hope to give our students are sets of skills that will prepare them for the unexpected.

One of the key failures of our educational system is that we structured it around routinized patterns that prepare our students for a world that doesn’t exist. Some students check out from clearly pointless routines. Others accept them and adapt their own patterns to match. Neither approach can solve complex problems. Getting through the routine motivates most of my students, not seeing what they can individually or collectively accomplish.

Perhaps most perniciously, they look upon collective effort with deep suspicion because the routine of education drives people toward zero-sum thinking. Whether you get through the system has little to do with whether I do.

This semester, and not for the first time, I had a student react strongly to the merest suggestion of graded group work. That’s because, inevitably, some percentage of the group will focus on the lowest common denominator necessary to “survive” the experience. The more engaged/savvy students don’t want to harness their wagons to drag those students along. They view peer learning as a trap.

Isaac Asimov’s “Profession” essentially parodies how far this kind of system can go. In his story, most “students” (they are programmed with knowledge instead of working for it) are directed, based on brain scans, to their “ideal” professions. They simply download the knowledge to carry out that profession into their receptive brains.

George Platen’s brain scans don’t conform to any pattern. The system relegates him to a “House for the Feebleminded” and he finds himself overcome by the shame of not being “allowed” to conform to the system.

Rereading this story just as the semester began really brought home to me the extent to which we mirror Asimov’s dystopian vision of education. I designed my class, within the constraints of the larger system, for the George Platens of the world. The rest of the system creates programmed individuals.

Unlike Asimov, I don’t believe that Platen is an exceptional case. I think everyone has, to a greater or lesser extent, a nonconformist impulse that results in creativity across a broad spectrum of activity. It’s just been buried by our closed loop education systems that emphasize conformity to process over creative, individualized approaches to learning.

These systems are no longer sustainable. Unbridled capitalism based on scarce resources has led to resource depletion, climate change and a general disregard for the needs of individuals. Many of the systems we are used to are not sustainable in this environment. Most of them were never equitable and depended on the exploitation of those less fortunate for their success.

In theory, learning represents one of the few open loops that exists in this paradigm. Open loops represent our best hope for navigating the thicket of challenges confronting our world. Over 75 years ago, Vannevar Bush recognizedthat closed-loop systems could neither manage the knowledge of the world nor the challenges that science and technology were creating. Following in Bush’s footsteps, Douglas Engelbart spent decades trying to apply technology to systematize open loop thinking, which he called “Collective IQ.”

Engelbart recognized that the fusion of technology with human collaboration was a means to bring humans to the level where they might confront the increasingly complex issues unleashed by the technology itself.

Consider a group's Collective IQ to represent its capability for dealing with complex, urgent problems – to perceive and understand them adequately, to engage the stakeholders, to unearth the best candidate solutions, to assess resources and operational capabilities and select appropriate solutions and commitments, to be effective in organizing and executing the selected approach, to monitor the progress, to be able to adjust rapidly and appropriately to unforeseen complications, and so on.

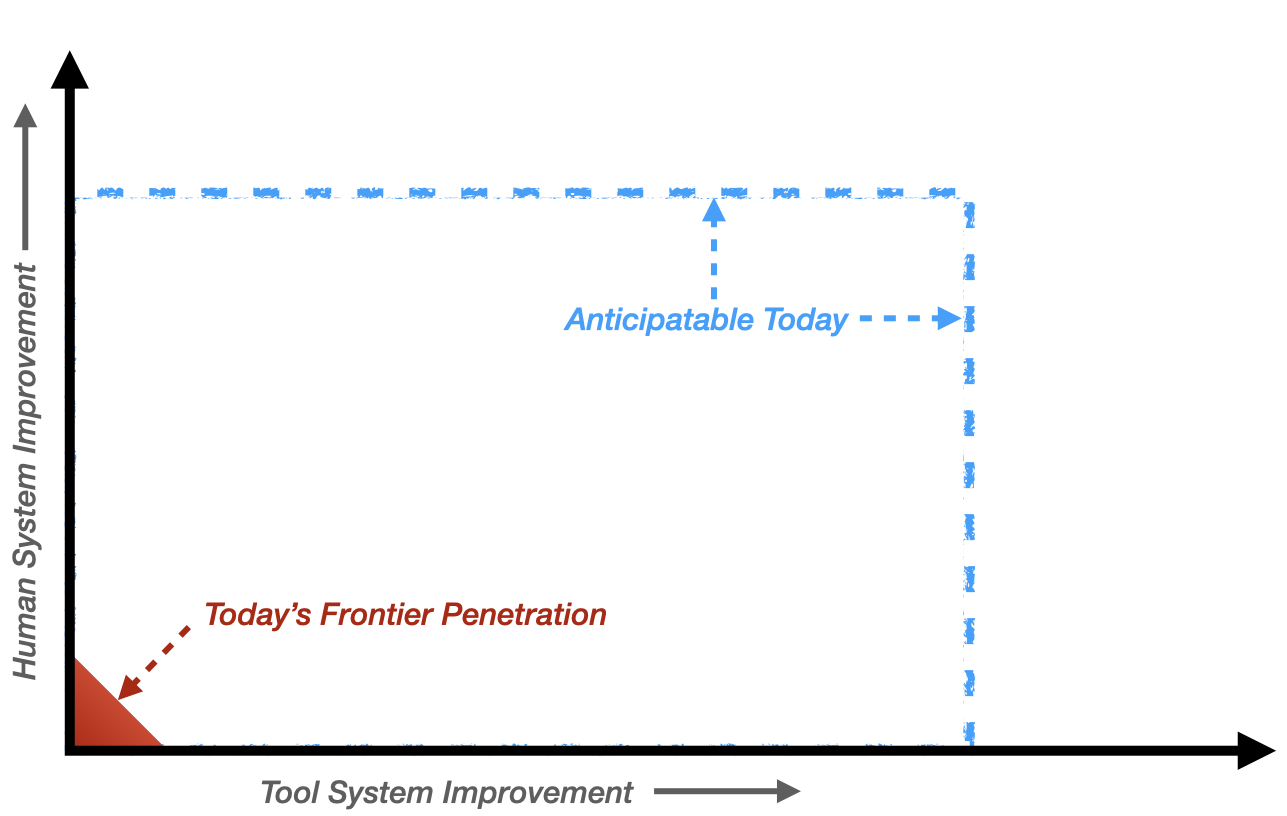

He argues that we grow Collective IQ by exploring the “anticipatable” horizon leveraging both technology and our human capacity for imagination. This is something I want my students to do, albeit on a much smaller scale.

Adapted from Engelbart

However, like Engelbart, I encounter resistance on a wide range of fronts, from institutions that are based on getting students through closed-loop systems of instruction to students who find the opened-ended nature of exploration disorientating.

These are issues that are difficult to resolve at the instructional level. The larger systemic context needs to support this kind of learning. This is a real challenge, as these systems are driven by larger societal factors, such as the “accountability movement,” that create perverse impulses toward closed loops.

If we hope to engage our societies in the project of Collective IQ to solve our urgent and unraveling challenges, we need to start with a realization of these interconnections and create systems of open loop learning. Our students are all different, even if they don’t want to be.